By ANAND GIRIDHARADAS

International Herald Tribune

Published: December 26, 2007

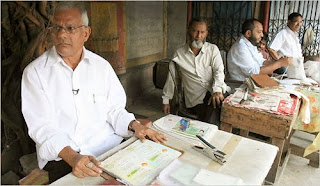

G.P. Sawant, 61, estimates that he has written more than 10,000 letters for people who were unable to do so.

MBAI, India G. P. Sawant never charged the prostitutes for his letter-writing services.

Not long after the women would descend on this swarming, chaotic city, they would find him at his stall near the post office, this letter writer for the unlettered. They often came hungry, battered and lonely, needing someone to convert their spoken words into handwritten letters to mail back to their home villages.

The letters ferried false reassurances. The women claimed they had steady jobs as shopkeepers and Bollywood stagehands. Saying nothing of the brothels, beatings and rapes they endured, they enclosed money orders to remit rupees agonizingly acquired. Many called Mr. Sawant "brother" and tied a string on his wrist each year in the Hindu tradition.

Sometimes, suspicious parents boarded a train to Mumbai and turned up at Mr. Sawant's stall, which a daughter had listed as her address. Mr. Sawant greeted them kindly but disclosed nothing about the woman's work or whereabouts.

Such is the letter writer's honor code: When you live by writing other people's letters, you die with their secrets.

But now the professional letter writer is confronting the fate of middlemen everywhere: to be cut out. In India, the world's fastest-growing market for cellphones, calling the village or sending a text message has all but supplanted the practice of dictating intimacies to someone else.

And so Mr. Sawant, 61, and by his own guess the author of more than 10,000 letters of others, was sitting idly at his stall on a recent Monday, having earned just 12 cents from an afternoon spent filling out forms, submitting money orders, wrapping parcels & the postal trivialities that have survived the evaporation of his letter-writing trade.

But this is not the familiar story of the artisan flattened by the new economy, because, it turns out, his family has gained more from that economy than it has lost.

Three of Mr. Sawant's four children are riding the Indian economic boom, including a daughter, Suchitra, who works at Infosys, the Indian technology giant. In the very years that a telecommunications revolution was squashing her father's business, it was plugging India into the global networks that would allow her industry to explode. Suchitra now earns $9,000 a year, three times as much as her father did at his peak.

Globalization is said to create winners and losers. For the Sawants, it created both. And that duality reflects the furious pace at which entire professions are being invented and entire professions destroyed in the rush to modernize India.

There is, on one hand, a national quest under way to excise inefficiencies to cut out middlemen. As go the letter writers, so go bank tellers as India adopts ATM's, phone-booth operators as cellphones spread, and rural moneylenders as new Western-style supermarket chains start trading directly with farmers.

But for every occupation that vanishes, another is born. There are now mall attendants in a nation that until lately had no malls, McDonald's cashiers in a country where cows are sacred, and Porsche sales executives in a land where most people still walk. It used to be hard to obtain a computer or telephone line in India; the country now has more software engineers and call-center operators than just about anywhere else.

G. P. Sawant entered the letter-writing trade in 1982 when he won a government contract for a coveted stall inside the post office headquarters. Before long, he earned a reputation among illiterate migrants as a gifted writer of letters.

Many of the letters were instructions from urban breadwinners on how to spend the money they were remitting to the countryside. They included expressions of affection for family members for whom they toiled in Mumbai but whom they rarely saw. They warned relatives not to squander money. They asked about the health of the aged and the infirm.

There were some letters Mr. Sawant would not write. He refused, for example, to trade in romantic love. Love is fickle and dangerous, he said. Lovers lie; they cheat; they offer their love and rescind it. He refused to engage in chicanery on other people's behalf.

Posted by Clifford T. Jacobs

Have Pen, Will Write

.jpg)